Strikes: Teacher Plan

Lesson plan 1: Children as laborers

GOAL: Help students to understand that for much of history, they were considered a labor force. Their energies were not funneled towards play or even education, but to working. For many children, they worked long hours in unsafe conditions with their parents and siblings. The photos below of help to illustrate what these workers looked like.

What you'll need:

- Sixty to seventy pennies to hand out as “wages”

- A box of snacks that students can “purchase” with their “wages”

- Items for children's "employment" such as text books, rusty tools, rags/dry cloths

- A way to show or pass out the photos provided below

To begin the lesson divide students into teams of manageable size. This might be teams 3-4. Warn students that this task might be difficult, and it will be okay if they do not like it. The activity will not last for longer than 10 minutes. Once they have completed their task they will be "paid" for their work and can purchase snacks from a store you’ve set up for them. Tasks must be performed silently and without complain. If students complain or talk too much they will be “fired” and will not get paid. If they ask how much they are to be "paid" tell them it is simply 'more than they are being paid right now' or 'I'm sorry, but that has not been decided yet'. If they ask how much the snack costs, tell them that most snacks cost about 50 cents.

As an instructor you may choose any of the following tasks for students to do:

- Watch the window and count each car that passes and note it's color

- Set a team of students to hold open the door for any person who might come in and out.

- Set a team of students to carry several textbooks from one end of the room to another and pick up the textbooks on that side of the room and move them to the other

- Give students stained plastic dishes and a sponge or and instruct them to remove as much of the stain as possible

Be prepared for students to be emotional, bored, disinterested, or complain they do not want to do this anymore. Some students will not follow instructions, either because they are chatting too much with a friend or because they are not engaging in the activity. Remind them they're 'being employed' and encourage them to return to their teams. If they do not comply, you may tell them to have a seat off to the side, firing them from their “job.” Do not pay these students for their work.

Once the time is up, let children report their work. If they counted cars and colors, nod and write it on the chalk board or make note of it. If students opened the door for persons, ask them how many they opened it up for, make that note a well. If they carried text books, ask them how many round trips they made or how many stacks they carried and note it. If the students were asked to clean, inspect them and nod. Give no compliment for how well they did.

Tell students based on their performance you are now ready to "pay" them. Give each student 2 pennies.

At this time, instructors will pull out a box labeled store. The box should be full of snacks. Students can look through items, but given their wages, they will likely be unable to afford anything as each item should be priced around 50 cents.

Once students realize their “income” will not be able to purchase much, expect many students to become frustrated. Students can try to pool their pennies together, making it so perhaps a few teams together could purchase something. Others may ask to work more.

Ask some of these following questions

- Who feels frustrated now? Why?

- Who felt your pay was fair? Who felt the pay was unfair?

- How long would it have taken for each individual to earn enough to buy one snack?

- Have students calculate how long they would need to work to buy a snack. If each student received 2 pennies and they worked 7 minutes it means they would have needed to work 175 minutes to get a single snack – close to 3 hours. [2 hours and 55 minutes]

- How would you feel doing your ‘job’ for 3 whole hours? Would that be fun? Would it be worth it for a single snack?

- How would you feel if this was your job the whole school day?

- What do you think would have happened if all of you had refused to work? Together do you think you could have changed my mind about what I would have paid you for the cost of the snacks?

At this time, please direct students to their assigned chairs and distribute copies of the photos above or show them on a screen if you have the equipment. We have provided some background and potential questions you might ask to involve children in these photos.

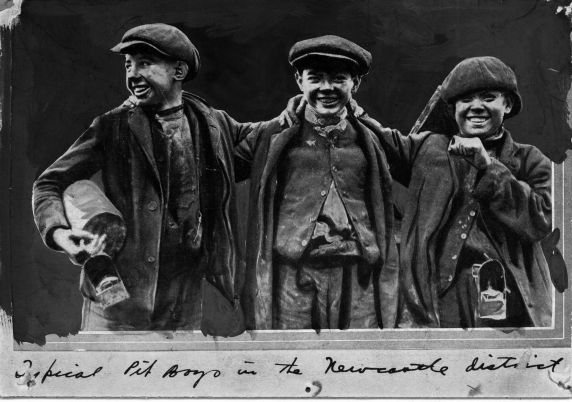

Details: Photographs of children identified as "Pit Boys" from the Newcastle District, Pennsylvania – 1910s – Reuther Library

Background information: Pit boys were young children who worked in closed shaft mining coal extraction. In closed shaft mining, a narrow channel would be dug into the ground to extract the coal that was near the surface. These channels were so narrow, only children could fit. The shafts had little ventilation and risked collapse. Trappers were also children who worked in open mines. Their job was to open and close the mine doors, so they sat for long hours in complete darkness alone, waiting for the light of mining carts to come by. Children in mine work could expect to work 12-14 hours in a day for maybe $1.13 but often quite less. The pit boys in this photograph range probably from 7-11 years old. Parents typically worked in the same mines as their children.

Ask the classroom: How old are the people in this photo? Where do you think they’ve been all day? What kind of work do you think they’ve been doing? What kind of clothes are they wearing? Where do you think their parents are? When do you think this photo was taken? Where was it taken?

Details: Children and adults harvest onions in a field, California. 1960s. Reuther Library.

Background: Similar to ‘pit boys’, farm children often worked along their parents for 12-16 hours days. Children on farms in Michigan might have been able to ear up to .83 cents a day but probably received closer to .20 or .50 cents. These children worked in the sun and rain carting water, weeding, harvesting, and carrying crops. Laws against child labor were different on farms than in mines in the U.S., as extensive child labor was used in farming industries up until the 1970s. Even today, migrant children often find themselves ‘helping out’ on the farms that employ their parents.

Ask the classroom: How many kids do you see in this photo and how old do you think they are? What do you think they are doing? Who do you think their parent and what is he doing? Why do you think one boy is not wearing a shirt? When do you think this photo was taken?

A possible way to end the lesson might be to say: “Children might also work in factories in cities like Flint, Detroit, or cities near Chicago, threading bobbins and cleaning small machinery for .25 cents a day. Children did not grow their hair in these factories, because their hair might be caught in the powerful machines. Often children fell ill from working such long hours, with little food and water and little access to recesses or breaks. They often had accidents and were sometimes seriously injured.

Many people, including many parents, just like your parents, said that this wasn't ok. They wanted children in their communities to go to school and be given time and space to be children. Many of these organizations were labor unions – people who worked with these children and banded together to make mines, factories, and farms safer for themselves while making sure kids would be kids. We have a whole holiday to remember their efforts during Labor Day here in the U.S.

Tomorrow we're going to learn about some of these organizations in Michigan and how kids like yourself were a part of those events which changed history.”

Possible homework: If you want to assign homework, you might ask children to ask their parents "how old where you when you first started to work and receive money.” These questions might generate conversations about working as teens or earning an allowance for chores.

Lesson plan 2: Strikes: Michigan

GOAL: The goal of this lesson plan is to illustrate some Michigan strikes and to help children understand how kids their age have been involved in strikes.

To begin: Take 5 minutes or so to review what they learned in class during lesson 1. You might ask, “Yesterday, we saw a bunch of photographs – who remembers those photographs? Who were in those photographs? What were those children doing? Who remembers the game we played yesterday? What was your job and how much did you get paid? Who remembers what you were able to purchase from the store? Do you remember me asking what would have happened if all of you had sat out of the activity?”

Next, explain, “Today, we’re going to learn about times here in Michigan when entire communities stopped doing their jobs to convince bosses to give better wages, safer working conditions, and shorter hours so they could spend time with their families. These organizations also argued that children should not be working – they should be going to school instead. To accomplish this, whole communities went on strikes.”

At this point, you’ll need to explain what a “strike” is to children. You might ask students if they know what a strike is, see if one of them can explain it, or perhaps someone can guess at what it is. You might explain that a strike is an event where communities of people who do the same job agree they won’t go to work until the leaders of a company fix problems. Often, these communities are called labor unions. Different types of jobs might have different labor unions. For example, there are labor unions of teachers, writers, and police officers.

Consider introducing the topic by saying: “Yesterday, we learned that many children were working long hours in mines, factories, and farms. Do you think those kids had any part in helping make these changes? They did!” Then pass out or show the photos below:

Details: Children carry pickets in support of the strikers on Women's Day during the Flint Sit-Down Strike, Flint, Michigan. 1937. Reuther Library.

Ask students: How many adults do you see in this photo? What ages do you think the children are? Which of the children stands out to you? What time of year was it? What do the picket signs say? Who were these children supporting?

Background: “Workers at the General Motors in Flint, Michigan were facing a consistent decrease in wages and an increase in work load, meaning people were doing harder longer work for less and less pay. Many could not afford food and homes for their families. On December 30th, 1936, assembly workers sat down on the job – and did not get up. This is known as a ‘sit down strike’ – a strike where workers sit down on the job and do not leave their place of employment. Workers did not leave the plant for 44 days. Can you imagine not leaving school for 44 whole days? Where would you sleep? Where would you get food? How would you change your clothes?

The families of the General Motors workers, largely women and children, arranged food and clothing deliveries to the workers and picketed outside of the plant. This photo shows one of their marches. On February 11th, 1937 General Motors reached an agreement with the workers, who were a part of a labor union known as the United Auto Workers or UAW. The UAW still exists today – many of you might have family who are members of the UAW if they work for General Motors or Ford.”

Details: Striking miners and their families gather outside of union headquarters in Calumet, Michigan. Reuther Library.

Ask students: How many people are in this photo? How many of them are children? Where are they? What time of year was it – how do you know?

Background: Copper Country, Michigan is located in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan which includes the cities of Keweenaw, Houghton, Baraga, and Ontonagon. It was called Copper Country because of the rich copper deposits throughout the region. Miners in Copper Country labored for very little pay in horrible conditions, working 10-12 hours a day. On July 23rd, 1913 around 9,000 miners walked out of the mines and began a strike – one where no miner would go back to work until their hours were decreased from 12 to 8 hours work day, their page was increased so they could afford food for their families at the store. They also asked for the mine to be safer. They wnated to become a part of a union called the Western Federation of Miners or WFM for short. This strike was not successful. On Christmas Eve, the WFM wanted to throw a Christmas party for the children of the Copper Country miners. With their parents not working, there was very little income and many of the children would not receive any presents for Christmas. But there was an accident in the building they were holding the party in and 59 children died. The miners were so discouraged by the loss of their children that they agreed to go and work back in the mines. The WFM was dissolved in Copper Country. Years later however, the WFM would reorganize as the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW-CIO) and this organization would help the Copper Country miners to reach their original goals.

For more information: http://reuther.wayne.edu/node/11098

Lesson Plan 3: Rights for Children

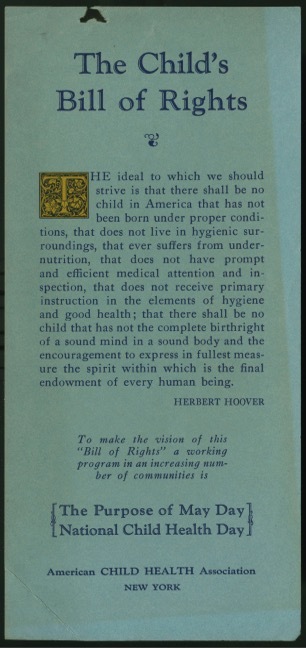

GOAL: The goal of this last lesson is to help introduce children to the Constitutional Bill of Rights and to compare it with the Child’s Bill of Rights by President Hoover. Until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 children would receive few protections legally in their work place and it was up to labor unions and civil organizations to push for children to be children rather than workers. One of the documents, which might have help make this cultural shift was the Child’s Bill of Rights. Below we have provided the language from the U.S. Constitution and a leaflet with Herbert Hoover’s Child’s Bill of Rights

To begin review some of the activities from the day before. Ask children if they can describe what a strike is or perhaps talk about the different kinds of strikes you discussed earlier.

“Children, like yourselves, would be used as a labor force in the United States with few legal protections until the passing of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. Important people, labor unions, and other community organizations pushed for legal changes in Congress protesting the severe treatment of children as workers. One such person was Herbert Hoover. Herbert Hoover founded the American Children’s Health Association and advocated for a day of play for children known as “National Child Health Day”. Below we’re going to get to see one of these leaflets and examine what Hoover believed were the “rights” of children.

Details: Scanned from the Merrill-Palmer Institute: Edna Nobel White Collection, series 1, box 24, folder 35, part 1. Reuther Library. Written by President Herbert Hoover and distributed by the American Child Health Association between 1927-1929.

Background: The Child’s Bill of Rights was written by Herbert Hoover, 31st President of the U.S. The American Child Health Association was an organization he founded in 1923. These flyers helped to raise awareness of the rights of children to healthy exercise, nutritious food, speedy medical care when injured and advocated for the humane treatment of children with disabilities.

The organization wanted “May Day” typically celebrated on May 1st, to be “National Child Health Day.” These leaflets would have been distributed to local community organizations such as ethnic and religious groups, schools, and labor unions to remind people to begin their planning for May Day. National Child Health Day was a time to celebrate the healthy development of a child from one year to the next. Essentially, this leaflet may be one of the first advertisements encouraging schools and communities to have “Track and Field Days” like the ones we have at the end of the school year in Michigan.

Activity: Have the children read each of the lines out loud together written by Herbert Hoover. List how many “rights” there are in the document and number them on the board. Ask students to write out which one of the “rights” from the Child’s Bill of Rights is most important and why – this activity will allow students to practice their writing skills, while also giving shy students an opportunity to reflect.

Activity: Ask students to imagine being able to send a letter back in time to themselves exactly one year ago. Encourage them to get their past self-excited for the new school year and all of the things they are going to learn and the friends they are going to make. These letters can be sent home with the children to their parents or brought up at parent teacher meetings. Additionally, a few of the most encouraging letter could be given to other teachers of grade below to help get younger students excited for their next year.

Ask students the following questions: Who wrote the Child’s Bill of Rights? Who was Herbert Hoover? Who distributed this information? When do you think this was written and distributed? Who did the Child’s Bill of Rights refer to when they said ‘There shall be no child that has not the complete birthright of a sound mind in a sound body’? How are these rights similar or different from the rights in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights? Whose needs do the Children’s Bill of Right focus on? Who do you think the audience was for American Child Health Association when they were distributing this information?

Possible Homework: Have students take copies of the Children’s Bill of Rights home to their parents and ask if they may read it out loud to them. Ask their parents if they agree or disagree with the values and protections Hoover wrote about? Why or why not?